Last Friday, August 15th, I had the honor to present at the IDSA International Conference in Austin about one of my favorite topics: Designers as Entrepreneurs. Here is a recap of my presentation.

Now is a great time to start a business. There is better access to capital, it’s getting easier to make and sell products, and there is a growing support network.

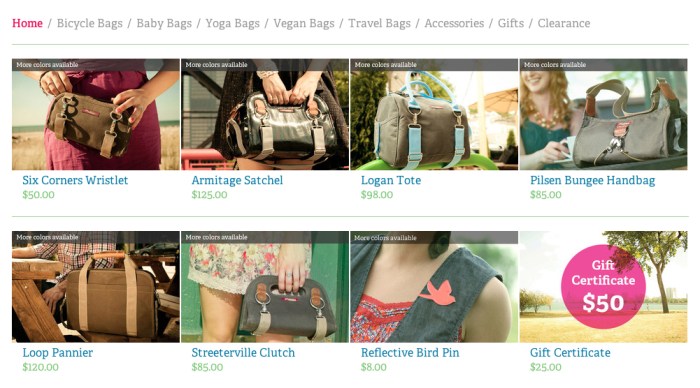

I launched my company Po Campo in 2009. We make bags for modern urban living: bike bags, yoga bags and travel bags. We sell our bags mostly through other retailers nationwide and internationally in Canada, Mexico, Europe and Australia, as well as through our online store.

There are lots of qualities that industrial designers typically possess that come in handy as an entrepreneur, particularly creativity, optimism and tenacity, because people are always going to be telling you that your idea isn’t going to work.

Yet there are other ways that I feel like my industrial design background has led me astray as I transitioned into the role of entrepreneur, which I’ll share through some anecdotes.

I had two jobs before Po Campo. I graduated from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2001 and wanted more than anything to become a design researcher. That was right after the first tech bubble burst though and jobs were hard to come by. I was thrilled to get a position at Arctic Zone, a Chicago-based manufacturer of soft coolers and lunch bags. That is where I learned cut-and-sew manufacturing and how to work with China.

Next I took a job at Webb deVlam, then called Webb Scarlett, as a structural packaging designer. In this role I learned about the power of branding, as well as the importance of standing apart from your competitors at shelf. Eventually I transitioned to heading Webb’s design research and design strategy department, focusing on helping our CPG customers identify white space in the market and learn what design language would communicate the desired benefits to the intended consumer.

Then I started to get the itch to do my own thing. As a consultant, I was working on projects for months that I cared deeply about, just to have them vanish with the final deliverable. I really craved holding onto the reigns longer. But doing what?

I always loved biking to work yet I wished there was a better way to carry my belongings. Backpacks and messenger bags didn’t do it for me and the bags that were designed to go onto bikes were very utilitarian. I felt like I was being made to choose between biking and having normal looks bags, which just seemed illogical.

I realized that with my background in soft goods design and branding, starting a bike bag company would be a perfect fit for my talents. Plus, when I started doing my market research, I learned that cities around the world were investing a lot of money to build up more bicycle infrastructure to encourage people to bike for transportation. I knew there would be a lot more people like me, looking for crossover products to help them integrate biking into their daily lives. I could claim this emerging market space as my own. Easier said than done!

I realized that with my background in soft goods design and branding, starting a bike bag company would be a perfect fit for my talents. Plus, when I started doing my market research, I learned that cities around the world were investing a lot of money to build up more bicycle infrastructure to encourage people to bike for transportation. I knew there would be a lot more people like me, looking for crossover products to help them integrate biking into their daily lives. I could claim this emerging market space as my own. Easier said than done!

I teamed up with a industrial designer friend and these were the first two products we developed, a “Going to Work Bag” and a “Going Out Bag”.

In the beginning, I was so excited about building a company led by two female industrial designers. I really believed in the power of design and thought that it would give us a tremendous competitive advantage. I was convinced that, compared to most companies run by old businessmen, we would do everything differently and everything better.

It wasn’t until I had to start doing all the other jobs in the business that I realized how wrong I was about the importance of the design. Everything from shipping logistics to accounting to customer service had a spirit of creativity and craft to it, especially in the start-up phase where you are building the company brick-by-brick and figuring out how it all fits together as you go.

This is Po Campo organization chart. Learning the other jobs within a company really leveled the playing field for me, which is why you see Design at the bottom with everything else, instead of at the top where I first thought it would go.

We launched in 2009, before Kickstarter and Shopify, so we went straight to selling in stores. I went door-to-door cold calling on shops. We got our bags into over 15 stores in Chicago that first summer and got great press right out of the gate. REI asked to bring in the line during our first month, and we soon had orders from Japanese and German distributors for our next season’s production run. Woo-hoo!

We started daydreaming about quitting our day jobs, about all the other great products we would develop, about what a cool studio space we would get. But that didn’t last long.

When I started calling our shops to get re-orders, I didn’t get any because they hadn’t sold any bags. After two and three months, they still hadn’t sold any, and would we mind taking them back? We panicked.

Looking back, I know what the two main problems were. First, our bags were about twice the price as the competition. Sure our bags were a lot cuter, as is evident in the photo above, but not THAT much cuter. Second, we were selling to an emerging market, which meant that our consumer not only did not know that products like ours were available, she didn’t even know that she needed a product like ours yet! We needed to do a lot more marketing that we hadn’t planned for.

Hindsight is always 20/20. At the time, we just felt like we needed to stop the leak and started asking our customers about what we could do to improve sell-through.

Most of the suggestions seemed like pretty simple fixes, such as streamlining the design to reduce cost, adding different sizes of bags, adding different colors, creating non-bike bags for people who like the look but don’t bike, etc. And here is where you have to be careful as a designer leading a company: Since design was the easiest thing for me to do, I just designed a lot more stuff. Our line ballooned from 6 SKUs to 68 SKUs just a few years later. Sure, we were growing, but it was haphazard growth that was hard to manage and almost certainly impossible to sustain.

Most of the suggestions seemed like pretty simple fixes, such as streamlining the design to reduce cost, adding different sizes of bags, adding different colors, creating non-bike bags for people who like the look but don’t bike, etc. And here is where you have to be careful as a designer leading a company: Since design was the easiest thing for me to do, I just designed a lot more stuff. Our line ballooned from 6 SKUs to 68 SKUs just a few years later. Sure, we were growing, but it was haphazard growth that was hard to manage and almost certainly impossible to sustain.

So I went back to my design background and thought about what I would’ve said to a client who would’ve approached me with a similar situation back when I was a design strategy consultant. I would’ve told her to reconnect with her consumer, so that’s what I did.

We started spending time with our core consumer, identified which values we were aligning on, and refocused our line-up and marketing strategy around those values. We realized that we were not just making bags but building a community around the joy of modern urban living. We’ve started doing a lot more events, selected our retail partners a lot more carefully and started creating videos to show how people can incorporate biking into their daily lifestyles easier. Sales continue to grow – sustainably.

We started spending time with our core consumer, identified which values we were aligning on, and refocused our line-up and marketing strategy around those values. We realized that we were not just making bags but building a community around the joy of modern urban living. We’ve started doing a lot more events, selected our retail partners a lot more carefully and started creating videos to show how people can incorporate biking into their daily lifestyles easier. Sales continue to grow – sustainably.

One of the biggest changes for me is learning to use numbers to understand what’s working in my business and what’s not, both for operations and design. Before Po Campo, I rarely used spreadsheets. Now data is my best bud.

I always liked design research because it enables you to make a sincere connection with the people you are designing for and helps you see how the products you are designing will make people’s lives better. But making people’s lives better isn’t enough to sustain a business; you also need revenue & profit. It took me awhile to really internalize that.

The design community doesn’t talk about sales much, as if talking about money that a product makes diminishes its value. I think this is a mistake, as it makes us think that good design is above trivial matters of money, when it’s not.

Part of the reason our line grew so big was that I got attached to the products that I want to have in market. I started my own company to make the products that I want in the world, so it is hard to kill them off. For products that didn’t sell well, I would always want to give them a second chance, thinking if I had marketed them differently, they would’ve sold better.

However, a bootstrapped company doesn’t really have the luxury to give products second chances. I’ve had to alter my definition of good design to be not just products that are made responsibly and meet a consumer need or desire, but also makes us money (preferably quickly and easily!).