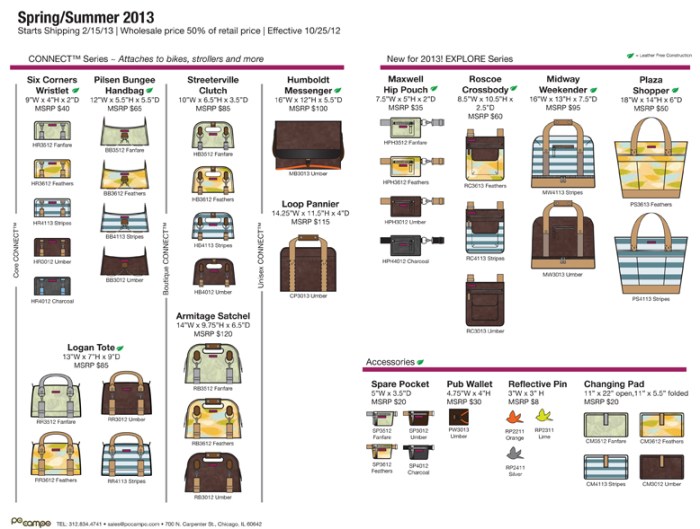

- Look at which bags sold the best this year and take the top 6.

- Look at which bags are going to be new for next year and take the top 6 that I’ve gotten orders for so far.

- Have a popularity contest. Tomorrow I will put these bags out on a table at during a Christmas cookie party of potential Po Campo consumers and have people pick their favorite three. I also plan to put a survey together online and blast it to the world – both consumers and customers

- Study the results, and pick 4-6 bags.

Author: Maria

Selfishly mentoring students

*Note: This is reposted from my entry on the Po Campo blog

I recently joined the mentor program at my alma mater, University of Illinois at Chicago, in which I meet with a small group of industrial design students every month or so to advise them on their studies. So far, as most other mentors say, I think it is helping me more than it helps them.

1) Makes me feel like I actually know something

It’s a purely selfish motivation, but it feels good to feel smart. Starting and running Po Campo has shown me how little I know because every day is filled with new lessons, mostly learned from making mistakes. But, working with the students, I feel like a genius! I’ve realized how much I’ve learned (and accomplished) since I was in their shoes as a sophomore in undergraduate studies.

2) Reminds me why I got into design in the first place

I fell in love with industrial design the moment I learned about it. I thought it seemed like the perfect job for someone like me, somebody who liked to make and sell things.

Now after working as a professional industrial designer for about 12 years, I appreciate the breadth of the profession. There are so many things you can do with ID training, from designing cell phones to museum exhibits to starting your own company (hello Po Campo!). All those possibilities begin with these first design courses, when you learn how to get the ideas from your head onto paper, and then learn how to evolve them and share them and – hopefully – make them real. My days are now filled with spreadsheets and supply chain issues, so it is enjoyable to table the “business side” of design for a little bit and just get into the nitty gritty of how to design something that looks nice and works well.

3) Teaches me how to teach

Before starting Po Campo, I worked at design agency Webb deVlam, where I held a senior position and would manage small project teams. Now, as owner and “boss” at Po Campo, I realize how easy I had it then. It’s much easier to manage people who are skilled, experienced, and doing a job you know how to do. It’s much harder to manage a small, inexperienced staff in doing a job you don’t really know how to do (or the best way to do it, anyway). See point #1 above.

Since the latter scenario is my new reality , mentoring this small group of ID students feels like teaching with training wheels. I am teaching something I know reasonably well but to a student who is very fresh, but also very eager to learn.

If I could impart one lesson, it would be to not get to discouraged and to keep at it. Despite being probably the coolest job on earth, industrial design careers tend to be rather bumpy and it can take awhile to find your place. But, perhaps that is how most things in life are.

Since I am new at this, I’m interested in hearing what your experiences are with teaching/mentoring or inspiring the next generation in your field. Please share in the comments below!

Finally, Something Good Happened!

The first 6-7 months of 2012 were pretty good, as far as sales were concerned anyway. I went into August with a full calendar of trade shows and a new sales team, pretty certain that I’d end the year just as strong as I started it.

But, I was wrong. Sales in August, September and October were about half as much as I was planning on, which was pretty devastating. Then my sales manager left (along with much of my sales team) when it became clear she wasn’t equipped to handle the problem. Then several stores returned their bags because they weren’t selling. Then I found out that one of our most popular styles was defective and that some customers were dealing with returns of up to 30%. Then I got turned down for a loan (after I was approved no less!) and I had to stop paying myself.

Finally, today, three good things happened.

1) The University of Chicago Business School is including Po Campo as a project case in their Marketing Research class! That means I am going to have 5 MBA students working on Po Campo for an entire quarter! This is too good to be true. Knock on wood.

2) I stood up to my manufacturer. I’ve been told I’m waaaay too nice and understanding and need to toughen up and be more forceful with my manufacturing partner, otherwise I’m just going to continue to be docked around. I really gave her a piece of my mind today, and it felt darn good. My intern said I sounded “assertive”, which is definitely a step up.

3) After seeing our bottom line go farther and farther into the red the last few months, I rolled up my sleeves to dig deeper into the Quickbooks file to see if something was wrong. I mean, I know things are bad, but really this bad? Good news, I found some oddity in the file that was having the cost of goods on some items be double what they actually were. In other words, it was only showing half as much profit as there actually should’ve been. After figuring out how to correct it, I improved our bottom line by $20,000! Hallelujah! (And why didn’t my accountant catch this?)

I hope this means that I’ve turned a corner. I’ve noticed my optimism increase as well as my general jolliness. Times sure can get bleak around a small company, but finding the patience and strength to wait it out and/or pull yourself back up can be certainly rewarding.

Failing Fast with Durable Goods

At a party last night, I was talking to friends about the big learning curve I’ve experienced with Po Campo. In short, at 4 years in, I feel like I need to rethink who my consumer is and what my distribution strategy should be. In some ways, it feels like going back to the starting line.

Agile Vs. Waterfall product development

My friend Randall, who works as a programmer, suggested trying the agile method commonly used by Web 2.0 developers, that encourages you to develop a product in quick iterations to “fail fast”. It is thought to identify and fix bugs faster and less expensively. Agile doesn’t have a definitive endpoint, you stop when you run out of time or when the product is good enough. This contrasts with the traditional waterfall method, in which development and management follow a sequential stage-gate process. For example, you know there will be, say, five phases of product development and what will happen in each phase and what criteria needs to be met before moving to the next phase. I grew up with the waterfall method in industrial design, which always made sense to me since there is more capital investment involved and more interdisciplinary stakeholders that need to be managed. You can’t pay to have a mold built and then decided you want to change it. And what about rapidly getting approval from marketing, engineering, procurement, logistics? That sounds like chaos!

I told Randall that it was hard for me to fail fast because it took a long time to get learning in the marketplace. By the time product is made and shipped to stores, 3-6 months have already gone by. We need another 3-6 months to see what consumers think, so my rounds of iterative development would be every 6-12 months – not very fast. Also, all of that less-than-perfect product would still be out there, potentially tarnishing my brand name. It’s not like I can just do a software update and bring everyone’s Po Campo bag up to the latest model. Retrieving them and replacing them would be too costly to consider.

Yet, I’m interested to see if there is a way to become more agile in product development. As consumers, we are getting accustomed to products being rapidly improved and the kinks worked out on an ongoing basis. There isn’t really any reason why this should stop with durable goods. One thing I like about cut-and-sew is how it is already inherently pretty agile, in that no new tooling is generally required and doing running changes is pretty acceptable. If agile was going to work with any manufacturing process, cut-and-sew would be the best fit.

What’s holding me back? I get confused with implementation. Most of our business is wholesale, meaning that we sell to other stores who sell it to the end user. They are a fairly traditional bunch and I know they would only want the latest and greatest. They also discourage change (even seasonly!) because it makes things harder for them to manage. Online sales seem like a better match because we can communicate with our end user and get feedback faster. Again, the bulk of our existing wholesale customers will push back against this, as they do not like product available online that they can not sell in their stores.

Has anybody else had success with implementing agile in their development of durable goods? I’m very interested to continue this discussion.

Mourning the loss of a business plan

For the last two months or so, every day seemed to bring bad news. I got turned down for a loan, my sales manager quit, a customer canceled an order, I didn’t have enough money to pay the bills, the Internet went out, my mother-in-law died, on and on. Even things that seemed like good news (“We got a large order for spring!”) became bad news in my head (“But I have no money to make more bags!”).

I was pretty gloom and doom, could hardly pull myself out of bed in the morning and wanted to just lie on the couch and drink boxed wine every evening. The whole starting-a-business thing started to feel like too much of a struggle, like maybe I wasn’t up for the challenge after all. It’s possible that I could fail, right? Is this what failure looks like?

I’ve gone through rough patches before, and would lie around and feel sorry for myself for a few days before finding the strength to “get back at it”. This time, that drive was slow to reappear. Each time I felt a little positive, something discouraging would happen that would send me right back to the couch. This time, the weight of despair felt heavier. I felt like I was in bereavement, buried under a heavy weight of sorrow.

But what was I mourning, exactly? I realized I was mourning the loss of a business plan.

I find business plans (and plans in general) a great source of comfort because they give you a sort of map to success. If checking off items from a to-do list gives you a sense of accomplishment and progress (like they do for me), they are great. But, as I learned this year, they also give you false hope because you say, “If I do X, Y and Z, this and this will happen”, but that’s not always true.

In my 2012 business plan, at this point, I was supposed to be sitting on top of a nice little pile of money – not a crazy amount, like $25,000, that I could use to buy more bags. I would have paid off one of my loans. I would have a small, but livable, monthly income. I would have orders booked for Spring 2013 for my new, big customers, like REI and Title Nine.

None of those things came true. Instead, I am struggling to find additional capital, have no monthly income and have to find new customers for next spring.

It dawned on me that it wasn’t so much the pitfalls of the business that were dragging me down, but more the feeling of being betrayed by my business plan. I trusted it to work and it didn’t and now I have no plan, no map to success. I was mourning the loss of my compass, my talisman.

So, what’s next? On my to-do list for this weekend is to start a new business plan for next year. This time I’m going to consider it a guide rather than a promise, and stay more vigilant about watching the story unfold rather than hoping that it will just all work out in the end.

I’m still on the hunt for my talisman, though.

4 Useful Things I learned while waiting tables

I designed something today and it was fun.

You’ve heard it before: if you want to spend your days designing cool stuff then you should get a job as a designer and not become a business owner.

When I started Po Campo, I was prepared to say adieu to my days at the sketch table for the opportunity to try and bring a good idea to market and make it a real business. For the first 2.5 years or so, I had a partner, a fellow industrial designer, who led the design and production efforts while I led sales and marketing. After my partner and I amicably split and I gained control of the whole company, I quit my day job to make time for my new responsibilities. I was excited to have design become become part of my daily job again, as I do love designing products, especially soft goods and especially bags.

Except it didn’t really turn out that way. It turns out that it takes a lot of money to start a business, which means sales and marketing always demand most of my attention, followed by thinking of ways to cut expenses. Whereas I used to preach to my clients about how important good product design was, and how its value warranted every hour I billed for it, I now consider it a “treat” for rewarding myself after spending a week doing things that I dislike, like cold-calling.

Recently, I indulged in some product design to develop Po Campo‘s Spring 2013 line. I turned off my email, turned off my phone, turned up the music, really worked out my ideas, and boy, was it fun. I put together a nice 23 page presentation about my inspiration, market trends, sketches and schematics and shared it with one of my buyers at REI. When we reached the end of the presentation, he said, “I can tell you really enjoy this stuff”. He’s right, I do. It beats the pants off of sales projections and cold-calling any day. It sucks that I can only do it 1% of the time. But it’s even more fun because I feel like it’s laying the foundation for my company’s success. Which means I still believe all those things that I used to tell my clients about how important design is, and that’s good. I’m glad that hasn’t changed.

“I never wanted to be a factory owner”

The title of this post is a quote from Annie Mohaupt, who owns Mohop! shoes. Po Campo shares a space with them in West Town. I recently overheard her say this to someone on the phone in an interview. She may sound regretful about having to transition from a DIY craftswoman to a true manufacturer, but I don’t think she is. She wants her business to grow and succeed, she wants it more than anyone else on this planet, so she is going to become a factory owner to make it happen.

When she said that, I got this familiar feeling I get when I think about my business sometimes. It is a blend of utter terror and thrill. Like maybe something you would feel if you were boarding a super fun roller coaster that people die on sometimes.

Usually I feel it when I sense something really good or really bad is about to happen. This time, I think I felt it because I have no idea of what my future holds. What will I have to become to have my business succeed?

One time in high school, at an overnight church lock-in, my friends and I went into the basement and stood in the middle of a long and wide corridor. We turned off all the lights and tried to see how far we could run at full speed before the fear of running smack into a wall would be too powerful to keep going. You wouldn’t believe how completely scream inducing and terrifying (and fun!) this was.

That’s kind of what I feel like starting a business is like and I don’t think it’s just my inexperience that makes me feel that way. (Read Wilson Harrell’s famous article on entrepreneurial terror here). I’m still running and hoping that my senses keep me from hitting a wall. If I manage to a get to a point where I haven’t killed myself and can turn on the lights, where will I be standing? And will I like where I am?

How I came to start my company

I’m an industrial designer by trade, which means my profession is designing new products that look great and work great. There are some people that may disagree with this simplified definition, but I think it sums it up pretty well.

I spent the bulk of the first 10 years of my career working for Webb deVlam, a design agency where we were hired to creatively solve problems for our clients. This was a fun job, kind of like Mad Men but without all the drinking and blatant sexism. Over time, I migrated from the core industrial design team to leading the strategy and research team, which turned out to be a better fit for me because I’m more of a big picture person and less of an anal detail oriented person.

In this role, my main responsibility was finding white space for our clients to explore and own. I found this to be quite fun because it’s like discovering uncharted waters where brands could really make a splash if they decided to go for the big business opportunity. In most cases, they didn’t because it was too risky and, instead, they thanked me and my team for our great ideas and filed them away somewhere. Regardless, I was always curious to know if our ideas would have made the big splash in the marketplace that I had imagined had they been implemented.